|

The Boston Mills Press |

|

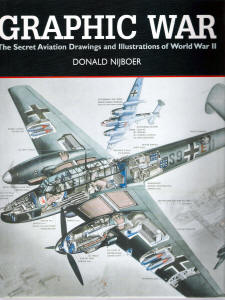

Graphic War The Secret Aviation Drawings and Illustrations of World War II |

|

by Donald Nijboer |

|

Reviewed By Art Silen, #1708 |

|

|

|

MSRP: $50.00 USD The Boston Mills Press, 2005 132 Main Street, Erin Ontario N0B 1T0, CANADA 272 pages; ISBN 1-55046-427-2 Donald Nijboer’s “Graphic War,” The Secret Aviation Drawings and Illustration of World War II” has a title that’s somewhat over the top insofar as it might suggest an OSS type of cloak-and-dagger intelligence-gathering operation, but the reality is much more mundane, but also much more important, as it is a primary reason why the Allies won the war. This is the story of the development of graphic illustration as instructional training aids, and that story is immensely important insofar as its contribution toward the Allies winning World War II. It is the story about the acquisition, transformation, and dissemination of technical information about the modern implements of warfare to millions of military personnel and their civilian auxiliaries as instructional manuals and training aids. As men and women joined their nations’ armed forces, they had to be taught the mechanical and functional components of modern warfare. This was accomplished through massive training programs supported by writers, graphic artists, specialists in book publishing, and military training officers, which produced uncounted millions of instructional manuals, posters, drawings, models, and other training aids, whose whole purpose would be to train former civilians, often indifferently educated and with no technical training or prior experience, into competent technicians, mechanics, maintenance personnel, and the many other forms of technical specialists required by the demands of modern warfare. Modelers of World War II era aircraft will want this book. I loved it; others will too, because as a detail nut, I look for airframe construction and equipment detail that can be simplified and reduced to its essentials. The posters and other graphic artwork describe and explain specific functionalities of airframe features and equipment, something not always discernible from photographs alone. At $50.00, this is not an inexpensive book, but it is really one of a kind. There are problems, however, and ultimately a sense of incompleteness that I will address more fully below. The first three chapters establish the historical basis on which this graphic artwork came into being. Nijboer begins his narrative by focusing on one individual who perhaps personifies the experience of many graphic artists and illustrators who were recruited into the war effort. Chapter 1, titled, “The Sword and the Pen”, is a short biographical sketch of Peter Endsleigh Castle who came to be employed as a technical investigator and graphic artist from 1938 until 1947. Modelers of a certain age will recognize Castle’s name, as he was a prolific artist and premier illustrator for many of the Profile Publications aircraft monographs that were produced from the mid-1960s until the early 1970s. In May, 1939, Castle attracted the attention of British MI6, when he was recruited for work at the Air Intelligence Branch. His job would be to make technical drawings of Luftwaffe aircraft, very little of which was known at that time. Castle’s drawings would be distributed to others for publication in recognition manuals and others charged with discovering and evaluating aircraft characteristics and capabilities. After the Battle of Britain, Castle was tasked with making cutaway drawings of Luftwaffe aircraft using information gleaned from shot down and captured aircraft. Often he had only twisted pieces of metal to work from. Once an aircraft was recovered, Castle and his colleagues would carefully measure it using tape measures. From these measurements, Castle would develop detailed three-view drawings. These drawings would eventually appear in aircraft recognition manuals or be used to make highly detailed models (in 1:72 scale, of course). Some of these models were painted in accurate camouflage colors and national markings, to be used to make photographs for inclusion in recognition manuals when clear, detailed photos of the actual aircraft were unavailable. In my library collection, I have a copy of the August, 1945, issue of Popular Science Magazine, where an article, “Navy Modelmakers Build Enemy Planes,” describes how a Navy model shop in Washington DC build exact replicas of German and Japanese aircraft just for that purpose. These models now form a part of the Smithsonian Institution’s model collection, and I was indeed fortunate to see some of them when I first moved to Washington in 1973. Peter Endsleigh Castle began making accurate cutaway drawings of German aircraft in 1942, beginning with the Dornier Do 217. That first illustration, dated June, 1942, was followed by others, including one dated August, 1944, of a Junkers Ju 188E-1. The results clearly show just how far Castle had perfected his skills as a draftsman in the space of two years. It was during that period that Castle was part of a team striving to uncover the secrets of the Fiesler Fi 103, known to all as the V-1, or Buzz Bomb. On November 28, 1943, an RAF Mosquito on a weather-aborted aborted photo reconnaissance mission to Berlin over flew the weapons-development installation at Peenemunde on the Baltic coast. Among the images captured on film was a tiny cruciform aircraft located on the lower end of a launch ramp, similar to those observed under construction along the French coast aimed at Southern England. Thus began a feverish effort by the RAF’s Central Interpretation Unit to identify the object and learn its particulars. Castle and RAF Squadron Leader Michael Golovine visited the Royal College of Science where he examined the captured film image on a microscope. Despite halation-caused blurring, Castle was able to calculate the object’s wingspan accurately to within nine inches of its actual seventeen feet six inches in measurement. Armed with this and additional information obtained from a crashed V-1 site in neutral Sweden, Castle was able to develop a drawing of the aircraft that was finally completed in July 1944. Regrettably, delays in printing prevented its issuance to Home Defense units until the following September. Nevertheless, this successful intelligence effort enabled Britain to successfully cope with the V-1 assault that began on June 15, 1944. Had it not been so, it is likely that the cross-Channel invasion would have been delayed or even postponed. Following Germany’s defeat, Castle and other investigators examined captured German aircraft. Kurt Tank was so impressed with Castle’s cutaway drawing of his Fw 190D-9 that he autographed it. Although most of Castle’s drawings are now lost, some survived and are now on display at the Imperial War Museum, in London. Chapter 2, “Today is not a Job”, describes wartime graphic illustration at the national level by Great Britain, the United States, Canada, and the Soviet Union. The author begins by describing the oft-times painful progress that each country had in transitioning from peacetime to wartime economies. Before the war, the RAF had only 14 aircrew training establishments, including one in Egypt. After the war began, the Luftwaffe could expect to train between ten and fifteen thousand pilots annually. By contrast, the RAF produced only 5,300 pilots in all of 1940. Development of adequate training facilities was of paramount importance, and these included instructional materials and training aids, if Great Britain were to survive as a fighting force. In the United States, the situation was similar. While American facilities were unaffected by immediate threat of enemy action, there was more to do. As training camps opened, the military was flooded with requests for training manuals and instructional materials, all of which had to be prepared, revised, and updated as weapons and materiel were being upgraded and refined. Some of these materials were rather crude, and yet others displayed exquisite detail and sophistication. In non-Western countries, graphic training aids varied widely (and wildly) in quality. The author has included a Chinese training poster from the 1930s illustrating anti-aircraft defenses. The quality of the rendering is good, even if the equipment it depicts was not. By contrast, the following page shows a crude pre-war drawing issued by the Soviet Union illustrating how fighters were supposed to intercept an attacking bomber force. Japanese technical illustrations were simple, but often crudely drawn. Chapter 3, “Lessons Learned – Into the Fire” discusses training of aircraft maintenance and ground crew, showing to how the job should be done. Included are schematic drawings for Beaufighter hydraulic systems, a graphically enhanced photograph of the P-38’s fuel system, and a simplified cutaway showing the P-61’s gunnery equipment and accessories. Here that the author could have done a great deal more to illustrate differences in national character and approaches to training programs. Each combatant had its own national style; British publications tended to offer good advice in a straightforward manner, but conveying a national sense of optimism about the war’s hoped-for outcome. American publications included appeals to patriotism, self-esteem, cartoons, and humor to make their point. The message was, every job was important, and everyone had an essential role to play. German publications were devoid of personality, but were of very high quality. I own a copy of the Aircraft Handbook for the Ju 188E-1, issued in September 1943. The drawings are technically excellent, but there are no cartoons, or morale-building features. When I assemble the Ju 188 kits I have in my cache, it will be a constant reference. Nevertheless, juxtaposition of British, German, and Russian contemporary illustration styles allow comparisons to be made. British graphic illustrations tended to be more artistic, detail-oriented and craftsman like, and more so the Germans. American drawings tended to be more utilitarian, emphasizing how subassemblies fit together to make a complete aircraft, epitomizing the American penchant for mass production. American instructional posters reflected their advertising heritage, showing primary colors and simple shapes. Among those included in the section on American subjects are engineering-style illustrations of the B-17G nose turret and gun-laying mechanisms and the bomb hoisting mechanism in the B-29. These were only as detailed as necessary to convey essential information, but otherwise unadorned. Cover art, such as that shown for the B-29 Gunner’s Information File manual also included in that section, sometimes tended toward impressionism, with gauzy renderings of aircraft in flight configuration, along with hortatory or morale-building statements. Inside the handbook, the artwork was essentially rendered as airbrushed silhouettes, essential information where necessary, and not much more. Soviet illustrations were even less detailed, and far cruder in execution. One can easily understand and sympathize with the problems Soviet training establishments faced in creating and disseminating technical information, except that the Soviet government put its primary efforts in graphic illustration into creating media focusing on patriotic and political indoctrination. Chapter 4 contains the image collection, drawn from British, German, American, and Soviet sources. Great Britain. The British collection is by far the largest; understandable as this is a Canadian publication and whose intended audience fought by and large under British colors. It begins with cutaway drawings of German designs, which, as mentioned, were derived from captured or wrecked aircraft that fell into British hands. These include the Messerschmitt Bf 109F, Bf 110G, Me 210 and 410; the Focke Wulf Fw 190A; Junkers Ju 88A-4 and Ju 88C (actually, it is the BMW 801-powered Ju 88R that is depicted) the Ju 87D; the Ju 188 (again, this is the E-1 variant with BMW radial engines); the Heinkel He 177 in its anti-shipping mode; the Henschel Hs 129 and the Fiesler Fi 103 Flying Bomb. Next we have a collection of British aircraft which includes the Lancaster Mk X (taken from the type’s maintenance and erection manual); a color drawing detailing construction features of the De Havilland Mosquito, along with another pen-and-ink drawing showing armament details; and a color drawing showing main construction features of the Handley-Page Halifax Mk III (Bristol Hercules radial engines). Then, we have a reprint of a drawing of a Japanese Frances twin-engine bomber, together with material from Aircraft Recognition, an inter-service publication published by the Ministry of Aircraft Production. This publication was intended to train service personnel in identifying Allied and enemy aircraft types, and included identification quizzes, along with graphic and descriptive materials. There are also multi-aspect drawings of various German and Italian maritime aircraft. Along with aircraft cutaways, there are drawings showing individual pieces of equipment, including exquisite multi-color drawings of the Colt-Browning .303 caliber and Lewis .303 caliber aircraft machine guns, instruction for gauging deflection shooting, cutaway drawings of mid-upper, lower, and tail gun turrets (Fraser-Nash and Boulton-Paul types). Super-detailers will swoon. Next come the heavy ordnance, 2,000-pound armor-piercing bombs, bomb fuses, depth charges, and aircraft torpedo cutaway drawings. Finally, there is a collection of instructional posters telling aircrew and other service personnel how to do their jobs while staying alive and safe while doing them. While some of them are humorous, all lend a sense of immediacy and reality to what was a very deadly endeavor. These instructions included getting home from a nighttime raid over Germany, air-sea rescue procedures, and ditching instructions for various aircraft types; aircrew clothing and equipment (diorama modelers, take note!); aero engine instructions and cutaways (Bristol Centaurus and Rolls Royce Griffon); and radio equipment. Germany. The German collection consists primarily of illustrations extracted from aircraft service manuals. These drawings are clear and consistently well done. Among the drawings included are cutaways of the Ju 87B and Ju 86D, and Focke Wulf Fw 58 (a small, twin engine utility aircraft on a par with the Avro Anson); a component assemblies breakdown of the Ju 87B (diorama guys, take note), and interior views of the Messerschmitt Bf 109F-1 through F-4, and the Dornier Do 217 N-1, the latter of which super-detailers will find most provocative. These drawings are on a par with well-drawn architectural plans, nothing spectacular, but of high quality overall. In recent years, some aviation illustrators, notably Arthur Bentley and Michael Merker, have done extraordinary work in detailing design features of specific aircraft types. While the wartime drawings are good, they are by no means as elaborately drawn or as detailed as those of more recent vintage. They were what they were intended to be, instructional media for busy and oftentimes overworked maintenance personnel who needed ready references for their unending tasks. Next, we have panoramic views of the pilot, bombardier, and radio operator/gunner positions for the Junkers Ju 88A. Next following is a poster-type diagram showing the procedure to be followed in initiating and completing a dive bomber attack by a Ju 88A. This in turn is followed by another Ju 88 cutaway poster detailing bomb and machine gun armament, again, a super-detailer’s delight. Several pages later there is a cutaway diagram for the Ju 88A-4’s electrical system. The German section concludes with armament drawings for the Heinkel He 111H-5, the Messerschmitt Bf 110C (four MG-17s), and the 50 millimeter cannon that armed the Me 410A-1/U-4. There is also a camouflage pattern (early) for the Heinkel He 177, a drawing of the MG 81 Zwilling twin machine gun, and two posters comparing Kriegsmarine and RAF Coastal Command flying boat aircraft. There is also discussion and several drawings of aero engines, including the Gnome-Rhone 14M used to power the Hs 129, the Daimler Benz DB 601E, (Bf 110, Me 210, and Me 410) and the Junkers Jumo 211 (Ju 88 and He 111), culminating with a cutaway drawing of the lubrication systems for the Jumo 211 and the BMW 801 (Ju 188 shown). Although lacking the personal immediacy of the preceding section, it is clear that German instructional materials were at least as good as their British and American counterparts. The forty pages next following give a sample of the output by the United States, concentrating primarily on Boeing and Consolidated Vultee aircraft products, specifically the Boeing B-17 and B-29 aircraft, and Consolidated’s B-24. Much of this has been published before. Except for technical illustrations showing various sub-assemblies, there’s not much of interest to modelers. Those interested in the technical details of American fighter aircraft might want to look at Francis H. Dean’s America’s Hundred Thousand; U.S. Production Fighters of World War II (Schiffer Military / Aviation History, 1997). For those with an in-depth interest in the subject, reprints of Pilot’s Manuals for various aircraft are still available from Aviation Publications, 3001 E. Venture Drive, Appleton, WI 54911. Check the publisher’s website for details (www.hbs.net/gcc/index.htm). These manuals are characterized by simple, yet effective graphics, pointed cartoons about dangers to be avoided, and simplified technical drawings and schematics showing how various systems worked. I recommend them to anyone wanting to learn more about the subject, and they’re wonderful source material for interior super-detailing. About seven or eight years ago I used the Flight Manual for B-24 Liberator (B-24D), no longer in print, to build the entire interior for my Academy B-24D. Beyond the immense satisfaction I got from recreating every visible portion of that airplane, I learned an enormous amount about how those airplanes were designed and assembled. Aircraft recognition manuals were drawn essentially the same way as technical manuals. A two-page spread from the U.S. Army Navy Journal of Recognition, circa Spring or Summer, 1945, depicts single engine and twin engine Japanese and American aircraft, 38 in all, in frontal profile. How effective such comparisons were in training service personnel to distinguish one from another is open to question. Some material included in the B-29 gunner’s handbook was definitely obsolete by the time it issued. American aircrew instructional materials used pointed humor to get their message across; navigators who caused their aircraft to run out of fuel over the ocean might end up sharing a life raft with angry, wet crewmen. Pilots hearing the sound of gunfire need not wonder where it was coming from; the poster warns that if they can hear it, it would be coming from right behind them, and very close. Color was occasionally used where black-and-white or halftone drawings might obscure essential functionalities or confuse readers. Whereas, a pen-and-ink drawing might be sufficient to instruct P-61 aircrew how to evacuate their ditched airplane, a four-color drawing of the evacuation sequence for B-17 aircraft, showing, in red, blue, and yellow, which crew stations evacuated first, who second, and who last. B-29s had separate emergency exit routines determining on whether the crew bailed out or ditched. Color was useful in showing diagramming airflow from engine air intake through the turbosupercharger, then through the intercooler, and finally to individual engine cylinders. A similar drawing appears showing fuel and air paths for the Bendix Stromberg Injection Carburetor. The Soviet Union. A very short section on graphic instructional materials produced by the Soviet Union completes the collection. Beginning with drawings of the engine and landing gear of the Ilyushin Il-2 “Shturmovik”, followed by a four-color panoramic view of the Il-2 cockpit, flight controls, armament controls, and pre-flight diagram. Next following are cutaway drawings of the Lavochkin La-7 single seat fighter showing its wooden fuselage and wing framing. Following that are drawings of the wing center section of the Petlyakov Pe-2 and the fuselage structure of the Ilyushin DB-3 bomber. The Pe-2 drawing is at or close to Western standard, but the DB-3 drawing is crude. Similar to the Pe-2 is a drawing of the internal wing framing for the Mikoyan MiG-3, highlighting its metal/wood center box wing spar and supporting ribs and stringers. There is also a diagram of the MiG-3’s welded steel truss center section. It would have been nice to see a discussion of how similar techniques were used by two of Great Britain’s most potent aircraft, the Hawker Typhoon, and its stable mate, the Tempest. Unfortunately, the book does not contain comparable drawings of the Hawker Hurricane, Typhoon, and Tempest. Two recent books do have reproduction of wartime drawings of steel tube framing of Typhoons (Leszek Moczulski, Hawker Typhoon, Part 2, AJ Press, 2004), and Tempests (Kev Darling, Hawker Typhoon, Tempest, and Sea Fury, The Crowood Press, 2003. While not a major point, it does highlight the tendency of the author to limit his discussion of aircraft or equipment depicted in the drawings, rather than comment on construction materials or techniques as between the major combatants. A bit of this appears in his captions on Soviet aircraft structural drawings, but much more could have been done to good effect. On balance, this book is very good, and it goes to the heart of what living was like during this period of our collective history. For modelers wanting to recreate artifacts of that earlier era, this book is really a “must have”, and I recommend it wholeheartedly. There are shortcomings, dictated, of course, by available materials, and the author’s (and his readers’) presumed interest, and it does seem that after touring British and German efforts, the author appears to have lost interest in his subject, and certainly with American subjects. The American section is a bit too abbreviated and focuses on too few aircraft types, or training styles. There could have been a greater discussion in depth about the burden of drawing, publishing, and distributing the enormous mass of information that industry and armed forces needed to prosecute the war effort. Information on German training aids is sparse almost to the point of non-existence. Other sources do exist to fill in the gaps, but as of now there appears to be no systematic way of organizing that body of knowledge. For example, in the Soviet section, there is some discussion of Soviet manufacturing techniques, principally the use of birch plywood to manufacture airframe components, and that it could not match later German airframe design. What is either not mentioned or if mentioned, it is not discussed at any length, is that all combatants began at a level of relative parity in aircraft manufacturing techniques and technology. Germany’s aircraft industry was further advanced than either Great Britain’s or France’s, but not by much, and the United States was not appreciably behind either Germany or Great Britain. The Soviet Union was much further behind any of the Western Powers, and for reasons specific to Stalin’s regime and its priorities, specifically Stalin’s overriding emphasis on development of heavy industry, and the regime’s political need to suppress potential opposition to its policies from educated Soviet elites. Germany led the world in aerodynamic science, but its manufacturing facilities, techniques, and most certainly its national priorities lagged behind those of Great Britain, and certainly those of the United States. The German High Command wasted enormous resources on projects that would have no impact on the outcome of the war: it could not field a strategic bomber in the same class as American and British heavy bombers, and had it perfected the He 177, there were insufficient national resources available to mount a bombing campaign in parity with the Allied effort; but perhaps most importantly, it failed to exploit the one weapon that could have had a strategic impact on the course of the war, namely its submarine fleet, when it had the opportunity to do so. In a war characterized by mass production and attrition as much as by invention, Germany could not hope to compete successfully with Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union either in quantities of arms produced, or in the trained manpower to use them. Much of Germany’s war-making potential came from countries it had over-run, Czechoslovakia and France, in particular, and Germany did not enter into a full war-time economy until 1943, but by then it was too late. Even the best trained, and best equipped troops could not compete against enemies whose strength was growing monthly, and by 1943, Germany’s opponents were at least its equal in most categories, and were surpassing it in offensive capability. Germany had a five-to-six year head start in preparing for the war it eventually launched, yet it squandered that lead by predicating its strategy on a short war in which technical and tactical superiority would overwhelm its unprepared opponents, to be followed by a dictated settlement. In the first year of the war, that strategy worked, but in the long run, when it became clear that the Allies were ready to fight for however long it would take to defeat the Axis Powers, Germany could not hope to succeed. For the Allies, the learning curve was steep, painful, and often deadly; but learn they did, and within a remarkably short time, they overcame Germany’s initial materiel advantages, but more importantly, by fielding highly trained personnel whose technical competence was second to none. Ironically, it was the Luftwaffe, when it began to suffer severe attrition in the spring of 1944, that sacrificed its training establishment, as flight training was curtailed and seasoned veterans were kept at the front until killed or were too badly injured to fly; before long, the quality of newly-trained replacement pilots declined so that newcomers might expect to engage in perhaps two or three combats before being shot down, wounded, or killed. All combatants began with small cadres of trained engineers, aircraft workers, and military personnel; even Germany, who began the conflict, had a relatively small workforce in comparison with its overall population, and the mechanized portion of its army was relatively small in comparison with the rest. As the war grew in intensity and sophistication, each of the warring powers drew upon thousands of people having no prior experience in either aviation or manufacturing to enter the workforce and to create machines and manufacturing techniques that could not have been envisioned before then. If anything, the graphic illustrations his book contains show ordinary people successfully adapting to a wartime environment, and how successfully they were able to assimilate the training that these graphic materials were intended to convey. |

|

Information, images, and all

other items placed electronically on this site |